In mechanics, a couple is a system of forces with a resultant (a.k.a. net, or sum) moment but no resultant force.[1] Another term for a couple is a pure moment. Its effect is to create rotation without translation, or more generally without any acceleration of the centre of mass.

The resultant moment of a couple is called a torque. This is not to be confused with the term torque as it is used in physics, where it is merely a synonym of moment.[2] Instead, torque is a special case of moment. Torque has special properties that moment does not have, in particular the property of being independent of reference point, as described below.

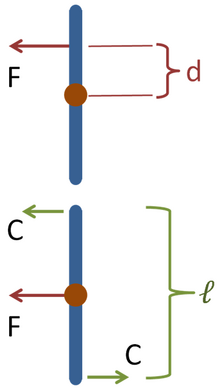

Simple couple

The simplest kind of couple consists of two equal and opposite forces whose lines of action do not coincide. This is called a "simple couple".[1] The forces have a turning effect or moment called a torque about an axis which is normal to the plane of the forces. The SI unit for the torque of the couple is newton metre.

If the two forces are F and −F, then the magnitude of the torque is given by the following formula:

where

- τ is the torque

- F is the magnitude of one of the forces

- d is the perpendicular distance between the forces, sometimes called the arm of the couple

The magnitude of the torque is always equal to Fd, with the direction of the torque given by the unit vector  , which is perpendicular to the plane containing the two forces. When d is taken as a vector between the points of action of the forces, then the couple is the cross product of d and F.

, which is perpendicular to the plane containing the two forces. When d is taken as a vector between the points of action of the forces, then the couple is the cross product of d and F.

[edit] Independence of reference point

The moment of a force is only defined with respect to a certain point P (it is said to be the "moment about P"), and in general when P is changed, the moment changes. However, the moment (torque) of a couple is independent of the reference point P: Any point will give the same moment.[1] In other words, a torque vector, unlike any other moment vector, is a "free vector".

(This fact is called Varignon's Second Moment Theorem.)[3]

The proof of this claim is as follows: Suppose there are a set of force vectors F1, F2, etc. that form a couple, with position vectors (about some origin P) r1, r2, etc., respectively. The moment about P is

Now we pick a new reference point P' that differs from P by the vector r. The new moment is

Now the distributive property of the cross product implies

However, the definition of a force couple means that

Therefore,

This proves that the moment is independent of reference point, which is proof that a couple is a free vector.

[edit] Forces and couples

A force F applied to a rigid body at a distance d from the center of mass has the same effect as the same force applied directly to the center of mass and a couple Cℓ = Fd. The couple produces an angular acceleration of the rigid body at right angles to the plane of the couple.[4] The force at the center of mass accelerates the body in the direction of the force without change in orientation. The general theorems are:[4]

- A single force acting at any point O′ of a rigid body can be replaced by an equal and parallel force F acting at any given point O and a couple with forces parallel to F whose moment is M = Fd, d being the separation of O and O′. Conversely, a couple and a force in the plane of the couple can be replaced by a single force, appropriately located.

- Any couple can be replaced by another in the same plane of the same direction and moment, having any desired force or any desired arm.[4]

[edit] Applications

Couples are very important in mechanical engineering and the physical sciences. A few examples are:

- The forces exerted by your hand on a screw-driver

- The forces exerted by the tip of a screw-driver on the head of a screw

- Drag forces acting on a spinning propeller

- Forces on an electric dipole in a uniform electric field.

- The reaction control system on a spacecraft.

In a liquid crystal it is the rotation of an optic axis called the director that produces the functionality of these compounds. As Jerald Ericksen explained

- At first glance, it may seem that it is optics or electronics which is involved, rather than mechanics. Actually, the changes in optical behavior, etc. are associated with changes in orientation. In turn, these are produced by couples. Very roughly, it is similar to bending a wire, by applying couples.[5]

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ a b c Dynamics, Theory and Applications by T.R. Kane and D.A. Levinson, 1985, pp. 90-99: Free download

- ^ Physics for Engineering by Hendricks, Subramony, and Van Blerk, page 148, Web link

- ^ Engineering Mechanics: Equilibrium, by C. Hartsuijker, J. W. Welleman, page 64 Web link

- ^ a b c Augustus Jay Du Bois (1902). The mechanics of engineering, Volume 1. Wiley. p. 186.

- ^ J.L. Ericksen (1979) Timoshenko Acceptance Speech at iMechanica.org site for mechanicians

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

|

| History of classical mechanics · Timeline of classical mechanics |

No comments:

Post a Comment